Progressive Overload with Squat Rack Barbell Weight: A Practical 12-Week Plan for Safe Strength and Hypertrophy

Programming Squat Rack Barbell Weight for Progressive Overload

Progressive overload with the squat rack barbell weight is the foundational strategy for consistent strength and hypertrophy gains. For most lifters the primary variables are load (weight on the bar), volume (sets x reps), frequency (sessions per week), and intensity (percentage of one-rep max). Practical programming balances these variables so the barbell weight in the rack increases predictably without compromising technique or recovery. Beginners can often add 2.5–5% to total load weekly; research shows novices may increase squat 1RM by 10–20% in 8–12 weeks under structured programs. Intermediates typically progress in smaller increments—~1–5% monthly—requiring autoregulation and deload weeks.

Start by establishing a reliable baseline: a tested or estimated one-rep max (1RM) and a working set weight where you can complete targeted reps with good form. Example: if a lifter’s estimated squat 1RM is 300 lbs, a conservative working set at 80% (240 lbs) for 5 reps is a common starting intensity. Use percentage-based programming (70–85% for strength phases, 60–75% for hypertrophy) and apply small increments (2.5–5 lbs) rather than large jumps to reduce injury risk.

Implement these best practices when handling squat rack barbell weight:

- **Warm-up progression**: 1) empty bar x 10; 2) 50% working weight x 5; 3) 70% working weight x 3; 4) working sets.

- **Microloading**: Use 0.5–2.5 lb fractional plates if possible to add minimal increments—this helps maintain linear gains, especially on the bench and squat where 5 lb jumps are significant.

- **Volume manipulation**: Alternate weeks between heavy (low-rep) and moderate (higher-rep) to stimulate strength and hypertrophy. Example pattern: Week A (5x5 at 75–80%), Week B (3x8 at 65–72%).

- **Frequency**: Squatting 2–3 times per week (1 heavy, 1 technique or accessory) results in better long-term adaptation than once-weekly maximal sessions.

Track metrics beyond raw weight—rate of perceived exertion (RPE), bar speed (if possible, with a velocity device), and recovery markers (sleep, soreness). A practical rule: if RPE increases by more than 1 across sessions at the same weight, hold load constant or drop 5–10% for a reload week. For athletes, combine daily undulating periodization (DUP) with a squat rack by varying intensity and rep ranges across the week; for general trainees, a linear 8–12 week progression with a planned deload every 3–4 weeks works well.

Step-by-Step Weight Progression Plan (12-Week Example)

Below is a reproducible progressive plan using squat rack barbell weight for a lifter with a 300 lb 1RM. The aim is sustainable weekly increases and measurable tests at week 12.

Weeks 1–4 (Base/Accumulation): Focus on volume and technique. Work sets: 4x6 at 65–72% (195–215 lbs). Progression: add 5 lbs to working weight every 7–10 days if all reps completed with good form. Accessory: Romanian deadlifts 3x8 and lunges 3x10 per leg.

Weeks 5–8 (Intensity Build): Shift to heavier weights for strength. Work sets: 5x5 at 75–80% (225–240 lbs) on heavy session; 3x8 at 65% (195 lbs) on technique session. Progression: add 2.5–5 lbs each heavy week. Introduce pause squats 2x3 at 70% once per week to improve positional strength under fatigue.

Weeks 9–11 (Peaking): Reduce volume, raise intensity. Work sets: 3x3 at 85–90% (255–270 lbs) week 9, then test week 11 with singles at 92–95% leading to a 1RM attempt in week 12. Deload (week 10) with 60% volume to recover if bar speed declines. Recovery strategy: prioritize sleep (7–9 hours), protein intake 1.6–2.2 g/kg, and mobility 10–15 minutes daily.

Week 12 (Test and Analysis): After two easy days and a mobility session, attempt a new 1RM. Expect realistic improvements: 5–12% 1RM increase for well-programmed beginners; 2–6% for intermediates. Record results, bar speeds, and RPE to inform the next cycle.

Safety, Setup, and Real-World Case Studies with Squat Rack Barbell Weight

Handling squat rack barbell weight safely requires correct equipment setup, consistent technique, and contingency planning. Start by setting the J-hooks so the bar rests at mid-chest when standing under the bar—this allows for an efficient unrack and minimal upper-body strain. Safety pins or spotter arms should be adjusted to catch the bar at or slightly below the bottom of your deepest safe squat. For visual setup, imagine a line where the bar clears the rack by 1–2 inches at the top of the lift and returns to the same line on descent; pin height should allow that path without letting the bar clip the rack on descent.

Key safety and setup checklist for managing barbell weight in the rack:

- 1. J-hook height: set at mid-chest to facilitate a smooth unrack and rerack.

- 2. Safety pins: set just below your lowest safe depth to catch a failed rep without impeding descent.

- 3. Collar use: always use collars for heavy sets to prevent plate slide; for top singles, secure plates tightly.

- 4. Footwear and stance: flat-soled shoes or lifting shoes as appropriate; stance width should allow knee travel and depth without valgus collapse.

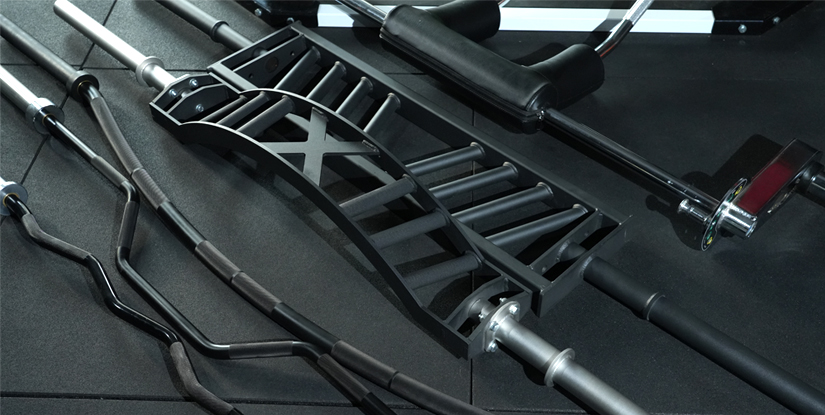

Real-world equipment choices affect how you load the squat rack barbell weight: Olympic bars rated 700–1,500 lbs are common; standard bar flex affects perceived load—stiffer bars feel heavier for a given weight. Fractional plates (0.5–2.5 lb) are especially valuable for precise progression; in competitive powerlifting, 1–2.5 kg increments are standard in many federations and permit conservative increases that sustain long-term progress.

Case Study: 12-Week Strength Cycle — From 300 lb to 334 lb 1RM

Subject: 28-year-old intermediate lifter, training 4 days/week, initial squat 1RM 300 lbs, bodyweight 200 lbs. Goal: increase 1RM while maintaining hypertrophy. Program: DUP-style 12-week cycle with two squat sessions per week—one heavy (3–5 reps) and one volume (6–8 reps). Nutrition: 300 kcal surplus with 1.8 g/kg protein. Recovery: 8 hours sleep nightly, soft-tissue work twice weekly.

Progression: microloading using 1.25 lb plates allowed 2.5–5 lb weekly increases in lighter weeks and 1.25–2.5 lb increases before peak. Adjustments: week 6 showed stagnation and elevated RPE; coach implemented a 7-day taper and swapped front squats for a week to maintain intensity while reducing axial load. Results: at week 12 the athlete achieved a 1RM of 334 lbs (+11.3%). Measured bar speeds increased by ~0.05 m/s on heavy singles and perceived soreness decreased after two planned deloads. Lessons: microloading, scheduled deloads, and accessory balance (posterior chain strength work) were decisive in converting steady increases in squat rack barbell weight into measurable 1RM gains.

Practical tips for coaches and lifters:

- Use objective markers (bar speed, rep completion rate) to decide when to add weight to the squat rack barbell weight.

- Incorporate mobility and technique sessions separate from maximal loading days to protect joints and reinforce form.

- When in a training block with multiple athletes, standardize J-hook and safety pin heights by marking positions on the rack to prevent inconsistent setups.

FAQs

-

How much squat rack barbell weight should a beginner start with and how quickly should they increase it? A beginner should begin with conservative loads that allow technical mastery—typically 50–70% of an estimated 1RM for working sets. For a true novice, weekly increases of 2.5–5% in total training load are reasonable; practically this can mean adding 5 lbs to the bar for lower-body lifts each week if form remains sound. Use RPE 7–8 as a guide: if sets feel like RPE 8 and all reps are clean, add the small increment next session. Monitor recovery—if sleep, appetite, or performance decline, revert to the previous week's load or insert a light week.

-

What are safe progression rates for intermediate and advanced lifters using a squat rack? Intermediate lifters should expect slower progress: 1–5% increases per month are normal. This often requires microloading (1–2.5 lbs or 0.5–1.25 kg increments) and periodization (blocks of accumulation, intensification, and peaking). Advanced lifters progress through planned cycles with multiple deloads and technical variations (paused squats, banded squats) to target sticking points. Advanced athletes should rely more on autoregulation metrics like RPE, bar velocity, and weekly volume distribution rather than fixed weekly percentage jumps.

-

How do I set up a squat rack for the heaviest barbell weight I plan to use? Set J-hooks at a height where you can unrack the bar smoothly without standing on toes—typically mid-chest. Place safety pins 1–2 inches below your safe lowest depth so a failed rep is caught before the chest contacts the pins. Load plates evenly and secure collars to prevent shift. When training maximal singles, have a competent spotter or use spotter arms that can safely bear the full rack load. Do a slow rehearsal with an empty bar to confirm path and clearance before heavy attempts.

-

When should I use fractional plates for squat rack barbell weight increases? Use fractional plates when standard 2.5–5 lb jumps are too large to maintain consistent progress—this is common for bench and squat once lifters reach intermediate levels. Fractional plates (0.5–2.5 lbs) are especially helpful during peaking phases where frequent small increases preserve neuromuscular adaptation without overtaxing recovery. They also allow more precise autoregulation when a lifter’s performance fluctuates week-to-week.

-

What are common technical errors when increasing squat rack barbell weight and how do I fix them? Common errors include losing lumbar bracing, knees caving (valgus), and shifting the bar path forward. To fix these: 1) reinforce bracing drills (diaphragmatic breathing and abdominal brace) between warm-up sets; 2) use accessory hip-dominant work (Romanian deadlifts, glute bridges) to strengthen posterior chain; 3) add paused squats and box squats to reinforce position at the bottom of the lift. Video analysis from multiple angles is invaluable—record sets to identify consistent breakdown points and address them systematically.

-

How often should I test a new 1RM when using squat rack barbell weight for programming? For most lifters, 1RM testing every 8–12 weeks is sufficient. Frequent maximal testing (> once per month) can impede recovery and make consistent progression more difficult. Instead, monitor submaximal performance (e.g., bar speed, reps in reserve) and schedule formal maximal tests at the end of a planned peaking block. Between tests, use heavy singles at 85–92% to gauge readiness without risking full attempts.

-

How do I balance hypertrophy and strength when programming the squat rack barbell weight? Combine phases: use higher-volume hypertrophy blocks (8–12 reps, 60–75% 1RM) to build muscle cross-sectional area, followed by strength-focused blocks (3–6 reps, 80–90% 1RM). During hypertrophy phases keep frequency at 2–3 sessions to maintain neuromuscular patterning, then shift to heavier, lower-volume sessions for strength. Accessory work should target weak points—quad-dominant exercises for knee drive, posterior chain work for lockout strength. Nutrition and recovery must align to the block’s goal—slight surplus for hypertrophy, maintenance for strength if weight class matters.

-

What role does squat stance and bar position play when increasing squat rack barbell weight? Stance and bar position alter leverage and muscle recruitment. High-bar (Olympic) squat typically uses a narrower stance and more upright torso, shifting stress onto quads; low-bar (powerlifting) uses a wider stance and greater hip hinge, engaging posterior chain more. A wider stance often reduces range of motion and may allow heavier loads for some lifters. Choose the variation that best transfers to your goals and practice it consistently—frequent switching during heavy loading phases can slow strength adaptations.

-

Are there specific mobility or warm-up routines recommended for handling increasing squat rack barbell weight? A targeted warm-up improves joint readiness and reduces injury risk. Begin with 5–8 minutes of light cardio and dynamic movements (leg swings, hip circles). Follow with joint mobilizations: ankle dorsiflexion drills, thoracic rotations, and banded lateral walks. Perform progressive loading sets: empty bar x 10, 50% working x 5, 70% working x 3, then working sets. Add specific mobility after the session for hips and ankles. For tight lifters, include daily 10–15 minute mobility sessions focusing on squat-specific limitations.

-

How should I adjust squat rack barbell weight if I feel signs of overtraining? If persistent fatigue, sleep disruption, elevated resting heart rate, or chronic soreness appears, reduce volume by 30–50% for 7–10 days or take a full deload week at 50–60% intensity. Alternatively, convert one heavy session to a technique or speed session at 50–60% with explosive intent to maintain neuromuscular drive while reducing systemic stress. Reassess nutrition and sleep and consider consulting a coach for programming adjustments.

-

Can the same squat rack barbell weight program be used for athletes in different sports? Yes, but adapt specifics to sport demands. Power athletes (football, rugby) prioritize maximal strength and often use lower-rep, higher-intensity work (3–5 reps) and more posterior chain emphasis. Athletes requiring endurance and repeated sprint ability may use higher volume and integrate metabolic conditioning. Transferable principles—progressive overload, technical precision, planned deloads—remain constant; sport-specific adaptations determine set/rep schemes, accessory selection, and timing relative to competition.