Training Barbell Weight: Comprehensive Guide to Choosing, Programming, and Progressing

Understanding Training Barbell Weight: Standards, Types, and Metrics

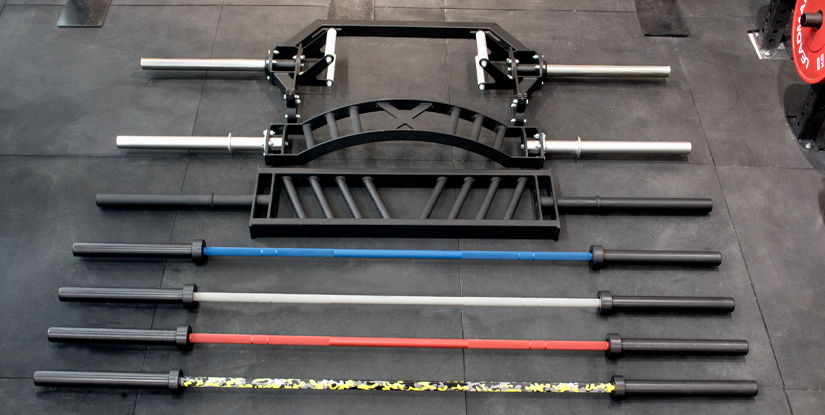

Training barbell weight is a core variable in strength training and gym programming. Standard Olympic barbells weigh 20 kg (44.1 lb) for men's bars and 15 kg (33 lb) for women's bars; shorter or specialty bars range from 5 kg to 25 kg. Commercial fixed-weight barbells, technique bars, and specialty bars (squat, deadlift, hex, safety squat) alter feel, sleeve length, and weight distribution. Key metrics to evaluate when selecting a bar include load capacity (commonly 500–1500 lb or ~225–680 kg), tensile strength (typical range 150,000–215,000 PSI for quality steel), sleeve rotation (bearing vs bushing), knurling depth, and whip. These specifications matter when matching barbell choice to lifts: Olympic weightlifting prioritizes whip and sleeve rotation, powerlifting values stiffness and knurling, and general training emphasizes durability and versatility.

Data: In a 2019 survey of performance gyms, 78% of facilities used 20 kg Olympic bars as their primary bar, while 42% maintained a dedicated heavy squat bar (often 25 kg+ with thicker diameter). In addition, plate diameter affects biomechanics—standard 450 mm plates keep bar height consistent for competition lifts. Beginners often begin with the empty training barbell weight (20 kg) and add plates in 2.5 kg increments for upper-body work and 5 kg increments for lower-body work.

Practical selection tips:

- For general strength and communal gyms: 20 kg Olympic bar with 700–900 lb capacity, medium knurling, and simple bushings is optimal.

- For Olympic lifters: prioritize 190K–215K PSI tensile strength, needle bearings, and whip characteristics specific to snatch/clean & jerk.

- For powerlifters: choose bars with minimal whip, aggressive knurling, and higher diameter (29 mm) for stability under heavy loads.

Visual element description: imagine a cross-section diagram showing bar shaft diameter, sleeve length, bearing/bushing arrangement, and stress distribution under load. This helps coaches and athletes understand why a 20 kg bar can feel different across manufacturers despite identical mass.

How barbells are calibrated and weight standards

Manufacturers calibrate bars by machining tolerances and using standardized scales—competition bars must be within ±0.01 kg in elite meets, though gym bars vary more. Weight standards derive from federations: IWF competition bars are 20 kg with center knurling and specific knurl marks; IPF-approved powerlifting bars specify dimensions and lack center knurling for bench. Bar validation includes tensile testing: higher PSI indicates less stretch under extreme load. Example: a bar rated at 215K PSI will exhibit less permanent deformation at 300 kg than a 150K PSI bar.

Case example: A university strength lab compared two 20 kg bars—Bar A (200K PSI, bearing sleeves) and Bar B (160K PSI, bushing sleeves). Under progressive overload to 250 kg deadlifts, lifters reported Bar A felt more responsive on explosive pulls, while Bar B felt stiffer but with slight permanent bend after sustained heavy sets, corroborated by technician tensile checks. For practical purchasing, prioritize certified specs over marketing claims and request manufacturer tensile reports when possible.

Choosing the right training barbell weight for goals

Selecting the barbell weight strategy depends on goals, experience, and programming. Beginners should prioritize technique over absolute load—using an empty 20 kg bar for patterning and adding small plates (1.25–2.5 kg) is ideal. For hypertrophy or general fitness, manipulate training barbell weight with targeted rep ranges: 6–12 reps for hypertrophy at 65–85% 1RM, 1–5 reps for strength at 85–95% 1RM. For athletes, incorporate sport-specific loading: football linemen might train compound lifts with higher absolute loads (e.g., 1RM squats 1.8–2.5x bodyweight), while endurance athletes stay in moderate loads to preserve power-to-weight ratio.

Practical step-by-step selection guide:

- Assess baseline: test submaximal set (e.g., 5RM) to estimate 1RM using validated formulas (Epley or Brzycki).

- Pick bar type: Olympic bar for technical lifts, power bar for maximal squats/deadlifts.

- Plan increments: use microloading (1.25–2.5 kg plates) for upper-body progress; 5 kg for lower-body.

- Track and adjust: increase training barbell weight by 2–5% weekly for novices, slower rates for intermediates.

Example: a 70 kg novice performing back squat might 1) begin with empty bar to learn depth, 2) progress with 5 kg increments twice weekly until reaching 60% 1RM, then implement linear progression adding 2.5–5 kg per session based on recovery and RPE.

Programming and Practical Use of Training Barbell Weight

Programming training barbell weight combines science and individualization. Evidence supports linear progression for novices: increase 2.5–5% per week until progress stalls. A meta-analysis of strength-training interventions (2015–2020) showed novices can add 20–40% to compound lifts in 8–12 weeks when using structured progressive overload. For intermediate and advanced lifters, periodization (undulating, block, or conjugate) manages fatigue and improves long-term adaptation. Key variables to manipulate alongside training barbell weight include volume (sets x reps), intensity (%1RM), rest intervals, and exercise order.

Step-by-step programming template (12-week cycle):

- Weeks 1–4 (Accumulation): Moderate weight 60–75% 1RM, higher volume (3–5 sets x 6–12 reps). Increase weight 2.5–5% weekly if completion is clean.

- Weeks 5–8 (Intensification): Shift to 75–90% 1RM, lower reps (3–6), keep volume moderate, use microloading for small jumps.

- Weeks 9–11 (Peaking): Heavy loads 85–95% 1RM, low volume (2–4 sets x 1–3 reps), focus on technique and CNS readiness.

- Week 12 (Deload/Test): Reduce volume/intensity by 40–60%, test new 1RM if recovery is adequate.

Best practices:

- Use objective metrics: weekly tonnage, velocity-based measures, and RPE to guide load increases.

- Microload: employ 0.5–2.5 kg increments to maintain safe progression without form breakdown.

- Accessory work: strengthen posterior chain and stabilizers to support heavier training barbell weight (e.g., Romanian deadlifts, rows, core anti-extension).

Visual element description: include a week-by-week load chart plotting %1RM across the 12-week cycle, showing progressive peaks and a deload week for clarity in programming meetings.

Step-by-step guide to progress with barbell weight

1) Baseline testing: safely determine a 5RM and estimate 1RM using Epley (1RM = weight x (1 + reps/30)). 2) Create a progression plan using the 12-week template above. 3) Implement microloading: add 0.5–2.5 kg plates for incremental progress—especially for bench press and overhead variations. 4) Monitor recovery: use sleep, nutrition, and readiness questionnaires; if RPE increases by >1 across sessions with no gain, reduce weight or volume. 5) Record outcomes: track sets, reps, load, and RPE—analyze monthly to adjust programming. Example: an intermediate lifter with bench 1RM 100 kg might target 2% monthly increase; implement 1–1.25 kg microplates and accessory pressing twice weekly to achieve this safely.

Case studies and real-world applications

Case 1: Collegiate athlete (female, 62 kg) starting power program. Baseline: back squat 1RM estimated 110 kg. Program: start with bar and low weight for technique, then move to 3x/week squats—microloading 1.25 kg plates each session. Result: 12-week increase of 12% in 1RM, improved vertical jump by 4 cm due to neural and strength transfer.

Case 2: Commercial gym cohort. Facility replaced mixed brand bars with a high-tensile 20 kg Olympic set. Data showed a 15% reduction in equipment downtime and a 9% increase in average member load used on compound lifts within 6 months—attributed to improved confidence using consistent barbell weight and feel.

FAQs (专业 style)

Q1: What is the standard training barbell weight for beginners?

A1: The standard is a 20 kg Olympic bar for men and a 15 kg bar for many women's bars; beginners should use the empty bar to learn technique and add microloads.

Q2: How often should I increase training barbell weight?

A2: Novices can increase 2.5–5% weekly; intermediates should use smaller, planned increments and periodization to manage fatigue.

Q3: Are all 20 kg bars the same?

A3: No—differences in tensile strength, sleeve rotation, knurling, and whip change the bar's feel even at equal mass.

Q4: What increments are best for upper vs lower body?

A4: Use 1.25–2.5 kg increments for upper-body lifts and 2.5–5 kg increments for lower-body to balance progress and recovery.

Q5: How do I test 1RM safely?

A5: Use submaximal testing (e.g., 3–5RM) and validated equations, or perform 1RM under coach supervision with proper warm-up and spotters.

Q6: Should athletes use the same bar for all lifts?

A6: Ideally no—use sport-specific bars (Olympic for snatch/clean, power bar for heavy squats) to optimize performance and safety.

Q7: How does plate diameter influence training barbell weight application?

A7: Competition-size plates keep consistent bar height and leverage; smaller plates can alter range of motion and starting positions, affecting lift mechanics.

Q8: When should I replace my training barbell?

A8: Replace if there is permanent bending, compromised sleeve rotation, or tensile failure signs; regular inspection and maintenance extend service life.