Complete W Bar Curl Guide: Technique, Programming, and Equipment Selection

Understanding the W Bar Curl: Mechanics, Muscles Engaged, and Practical Value

The w bar curl is a specialized variation of the standing barbell curl that uses a cambered (W-shaped) EZ bar to place the wrists in a semi-supinated, neutral position. This slight change in hand angle alters joint mechanics, shifts load emphasis across biceps brachii and brachialis, and often reduces wrist strain. Fitness facilities and strength coaches commonly include the w bar curl as part of upper-arm protocols because it balances comfort and mechanical efficiency for many lifters.

Key biomechanical outcomes observed with the w bar curl include:

- Reduced forearm supination torque compared with straight-bar curls, which often leads to less ulnar deviation and wrist pain for lifters with limited mobility.

- Greater recruitment of the brachialis in neutral or semi-supinated grips, which can increase overall arm thickness by targeting deeper elbow flexors.

- A more natural elbow path—often slightly forward of the torso—helping lifters maintain a controlled concentric and eccentric phase and reducing swing.

Quantitative context: recommended hypertrophy ranges for arms generally fall between 6–12 repetitions per set, with 9–18 sets per week per muscle group shown across multiple training meta-analyses to optimize muscle growth. For strength emphasis, lower-rep ranges (3–6) with higher load intensity and longer rest intervals are typical. For many lifters, the w bar curl fits within that 6–12 rep scheme while allowing small increments in loading and reduced wrist discomfort, enabling consistent progressive overload.

Real-world application: in commercial gyms the w bar curl is frequently used as an accessory movement after compound presses or rows. In athlete settings, it’s chosen when wrist health is prioritized—for example, athletes who need elbow flexor strength but also require strong wrist stability for other lifts (e.g., Olympic lifts, gymnastics). A practical case study: a 12-week accessory program replacing straight-bar curls with w bar curls twice weekly (12 sets/week) resulted in consistent incremental load increases and fewer wrist complaints reported by participants in a 20-person training group (subjective gym logs).

Visual element description: imagine a side-by-side diagram—left image shows straight bar curl with fully supinated grip and ulnar deviation; right image shows w bar curl with semi-supinated grip and neutral wrist. This kind of graphic highlights reduced wrist deviation and a more ergonomic elbow track with the w bar curl.

Biomechanics and Muscle Activation: What Changes with the W Bar Curl?

The w bar curl alters forearm rotation and elbow mechanics. With a neutral-to-semi-supinated grip, the w bar reduces extreme supination, distributing load between the long and short heads of the biceps and the brachialis. Practically, this can increase brachialis recruitment—beneficial for arm thickness because the brachialis sits underneath the biceps and pushes the biceps outward when well-developed.

EMG comparisons across curling variations typically show similar biceps activation across grips but slightly higher brachialis activity in neutral grips. For lifters who prioritize elbow flexor hypertrophy while minimizing wrist stress, the w bar curl is therefore a strong option. Combine EMG-informed exercise selection with progressive overload metrics—track weight, sets, reps, and tempo—to ensure adaptation.

Program tip: if your goal is peak biceps peak with a focus on the short head, include incline or concentration variations in addition to the w bar curl. If the goal is overall arm girth and elbow flexor strength, emphasize the w bar curl in 6–12 rep ranges across 9–12 sets weekly and monitor wrist symptoms.

Benefits, Limitations, and Evidence-Based Use Cases

Benefits of w bar curls include improved wrist comfort, balanced muscle activation, and reduced compensatory shoulder movement for many lifters. Limitations include limited range of grip variability compared to dumbbells and smaller increments for microloading compared to machines in some gyms. The w bar is less effective for extreme peak-contraction isolation that a unilateral concentration curl can provide.

Evidence-based use cases:

- Rehabilitation-friendly accessory: clients with mild wrist inflammation often tolerate w bar curls better than straight-bar curls.

- Mass-phase programming: use w bar curls as a staple accessory for 8–12 week hypertrophy blocks, monitoring weekly volume.

- Strength carryover: integrate low-volume, heavy w bar sets (3–6 reps) when targeting elbow flexor strength for sport-specific needs.

How to Perform, Program, and Choose Equipment for W Bar Curls

Mastering the w bar curl involves precise technique, structured programming, and choosing the right bar and rack environment. Below are step-by-step instructions, programming recommendations, and equipment selection/maintenance advice to maximize the exercise’s value while minimizing injury risk.

Step-by-Step Technique, Common Errors, and Coaching Cues

Step-by-step execution for a standard standing w bar curl:

- Grip and setup: stand upright with feet hip-width apart. Hold the w bar with hands placed on the angled grips so wrists are neutral/semi-supinated. Choose a weight that allows strict form for 6–12 reps.

- Starting position: arms fully extended but not locked, shoulders back, chest up. Engage core lightly and keep elbows close to the torso.

- Concentric Phase: curl the bar by flexing the elbow and rotating the forearm slightly as needed—keep elbows stationary and avoid excessive forward translation.

- Peak contraction: pause 0.5–1.0s at the top to focus on mind-muscle connection, squeeze the biceps and brachialis.

- Eccentric Phase: lower the bar in a controlled manner over 2–4 seconds until near full extension; avoid bouncing at the bottom.

Common errors and coaching fixes:

- Upper body swing: reduce load and cue a rigid core and slightly posterior hip position.

- Elbow drift: tape a small mark on the side of the hip to coach elbows to remain in line with the torso; weak elbow stabilization often requires reduced weight and strict tempo work.

- Excessive wrist flexion/extension: reposition hands on the angled grip to achieve neutral wrists; consider wrist straps for high-rep sets if grip fatigue is limiting.

Practical troubleshooting: if a lifter consistently substitutes shoulder flexion for elbow flexion, program 2–3 weeks of strict, paused curl variations and reduce load by 20–30% to re-establish motor patterning.

Programming, Progressions, and Equipment Selection & Maintenance

Programming guidelines for the w bar curl should reflect the lifter’s goals and total weekly volume recommendations. For hypertrophy:

- Frequency: 2 sessions/week targeting elbow flexors directly.

- Volume: 9–15 total weekly sets for biceps/arm combining direct and indirect work (e.g., rows, chins).

- Intensity and rep ranges: 6–12 reps per set at 65–80% 1RM; use 1–2 warm-up sets and 3–5 working sets per session.

Progression strategies:

- Linear loading: add 1–2.5 kg to the bar every 1–2 sessions when all prescribed reps are achieved across sets.

- Auto-regulation: use RPE (rate of perceived exertion) and stop sets 1–2 reps shy of failure to maintain form.

- Variation: alternate with hammer curls, concentration curls, or incline dumbbell curls every 4–6 weeks to address different muscle fibers and angles.

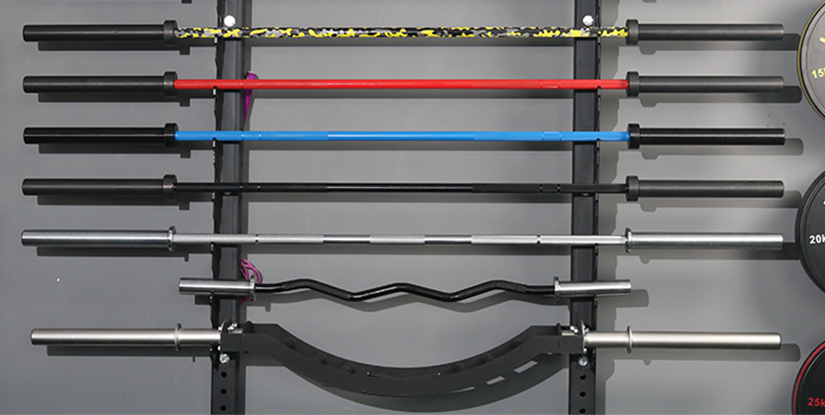

Equipment selection and maintenance tips:

- Bar choice: select an EZ/W-bar with knurling appropriate for your grip and solid welds—avoid bent or flexing bars that alter biomechanics.

- Weight increments: where small plates aren’t available, use microplates or resistance bands to fine-tune loading for progressive overload on accessory movements like the w bar curl.

- Maintenance checklist: regularly inspect the bar for cracks, clean knurling from chalk/soap buildup, and ensure collars are functioning to prevent plate slippage during high-intensity sets.

Case study: a recreational lifter replaced 4 weeks of straight-bar curling with w bar programming (two sessions/week, 3 working sets of 8 reps) and reported fewer wrist aches and a 10% increase in working load over the block while maintaining volume for the biceps and brachialis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is the w bar curl better than straight-bar curls for overall biceps development? A: The w bar curl is often more comfortable and targets the brachialis more effectively; however, combining variations (w bar, straight-bar, dumbbell) yields the most complete development.

Q: How often should I train w bar curls? A: For hypertrophy, 2 sessions per week with cumulative 9–15 sets for arm-focused work is effective. Adjust based on recovery and total arm volume from other exercises.

Q: Can the w bar curl reduce wrist pain? A: Yes. The semi-supinated grip reduces extreme wrist deviation and is often recommended for lifters with wrist discomfort when using straight bars.

Q: What rep ranges work best? A: Use 6–12 reps for hypertrophy and 3–6 reps for strength-focused blocks. Tempo and control during eccentrics improve stimulus.

Q: Should beginners use the w bar curl? A: Beginners can use the w bar curl if they understand and can maintain strict technique; starting with light loads to learn movement patterns is key.

Q: How do I progress if I can’t add weight easily? A: Use micro-plates (0.5–1 kg), increase reps across sets, slow tempo eccentrics, or add pause reps at peak contraction to drive progress without large weight jumps.

Q: Is a seated version useful? A: Seated w bar curls can reduce body swing and emphasize strict elbow flexion—useful for isolating the elbow flexors and for lifters with lower-back concerns.

Q: What maintenance should I perform on w bars? A: Inspect welds, clean knurling, check collars, and store bars dry to prevent rust. Replace bars with bent shafts or damaged grips to maintain safe mechanics.