Comprehensive Guide to Choosing and Using Weights for Standard Barbell

Overview: Understanding Weights for Standard Barbell

Selecting the right weights for standard barbell setups is foundational for safe progress, efficient programming, and long-term equipment value. A "standard" barbell typically refers to a 1-inch (25 mm) sleeve diameter bar used in many home gyms and older commercial sets. Unlike Olympic bars (≈2" sleeves, 44–45 lb), standard barbells often weigh between 12–25 lb depending on length and material. Plates for these bars are sized to fit that 1" sleeve and are sold in common increments such as 1.25 lb, 2.5 lb, 5 lb, 10 lb, and 25 lb. Knowing these specifications helps you plan loads, storage, and progressive overload strategies.

Real-world application: a small apartment gym with a 15 lb standard bar and plate set (1.25–25 lb) allows a user to progress from bodyweight-plus to intermediate strength levels for bench press and rows, but may limit heavy deadlifts or squats where larger plate diameters and barwhip of Olympic setups are beneficial. During the COVID-19 home-gym boom, retailers reported a 40–60% increase in demand for compact standard barbells and plates — a sign that space and budget constraints often drive the standard-bar choice.

When selecting weights for a standard barbell, consider three practical dimensions: load range, increment granularity, and material. Load range determines maximum achievable resistance; if you intend to train squats and deadlifts to high loads, ensure you can physically fit enough plate mass on each sleeve. Increment granularity affects progression: standard plate sets with 1.25 lb plates enable 2.5 lb total jumps (1.25 each side), which is sufficient for many lifters. Material influences durability and noise: cast-iron plates are economical, while rubber-coated and urethane options reduce floor damage and noise.

Best practices for purchasing and using standard plates include measuring your bar's sleeve length and diameter, verifying plate inner diameter (must match 1"), and prioritizing collars or spin-locks to secure plates. Practical tips:

- Buy a balanced set: equal plates per side to simplify loading and ensure balance.

- Start with a 100–150 lb total plate inventory for novice progress; add heavier plates later.

- Use fractional plates (0.5–1 lb) for microloading if standard increments feel too large.

Case study: A 60-kg recreational lifter began with a 15 lb standard bar and a 100 lb plate set. With structured linear progression (adding 2.5 lb total per week on main lifts), the lifter achieved a 20% strength increase in 12 weeks by leveraging 1.25 lb plates and prioritizing consistency over heavy top-end loads.

Types of Plates and Materials

Standard plates are available in several materials and designs. The most common are:

- Cast iron (bare): durable, affordable, and compact. Typically the least expensive option; excellent for static lifts. Prone to rust if uncoated.

- Enamel-painted cast iron: provides corrosion resistance and color coding; moderate cost.

- Rubber-coated or rubber-encased plates: quieter, protect floors, and reduce chipping; slightly bulkier and pricier.

- Urethane-coated plates: premium, highly durable, low odor, and minimal deformation; expensive but long-lasting.

- Fractional steel plates (thin disks): enable microloading (0.5–2 lb) for steady progression where standard jumps are too big.

Practical comparison: If you train in a shared apartment, rubber-coated plates reduce noise transfer to neighbors and help protect hardwood floors. For a garage gym exposed to moisture, enamel or urethane options resist corrosion. Budget-minded lifters who prioritize pound-for-dollar will often choose cast iron and pair it with protective rubber mats to prevent damage.

Quantitative note: a 25 lb cast iron plate typically measures ~1.5"–2" thick on a standard plate, while a rubber-coated 25 lb plate can measure 2.5"–3". Measure sleeve length on your standard bar to ensure the plates you buy will physically fit with collars attached; a short sleeve may limit usable plate count and therefore maximum load.

Buying tip: confirm inner bore diameter (should be ≈1.00" for standard bars). Some manufacturers list metric values; ask or measure. If you plan to add significant mass (e.g., for powerlifting training), consider upgrading to an Olympic setup for larger sleeve capacity and better bar dynamics.

Programming, Loading Strategies and Practical Use

Programming around weights for standard barbell systems requires managing increments, balancing progression speed with safety, and adapting training protocols to the equipment limitations. Standard plates often restrict maximum load by sleeve length and plate dimensions. For many users, the focus should be on consistent progressive overload, exercise selection, and rep scheme adaptation rather than absolute top-end numbers.

Rep-range strategies that work well with standard setups:

- Strength focus: 3–6 reps, 3–5 sets — progress with 2.5–5 lb total jumps weekly.

- Hypertrophy: 6–12 reps, 3–4 sets — use slower tempos and reduced rest to increase time under tension when plate increments are large relative to current strength.

- Endurance/metabolic conditioning: 12–20+ reps, circuits — less sensitive to exact weight increments.

Concrete loading example for a 20 lb standard bar: if a lifter bench presses 100 lb total (20 lb bar + 80 lb plates), increasing load by 5 lb total (2.5 lb per side) requires 2.5 lb plates. If those aren’t available, add 5 lb per side for a 10 lb total jump — too large for steady progression. Here, fractional plates or microloading is critical. Many lifters buy a set of 0.5–1 lb fractional plates to allow 1–2 lb total jumps.

Case study — program adaptation: An intermediate lifter stalled on bench press using a standard bar with limited sleeve room and only 5 lb and 2.5 lb plates. By incorporating eccentric tempo training, paused reps, and 1 lb fractional plates, the lifter regained linear progress without investing in a new bar. Over 8 weeks, bench press improved by 7–10% while training volume and technique adjustments compensated for small equipment constraints.

Best practices for balancing and plate configuration:

- Always load the same total on both sides; count plates, not just eyeball.

- Place larger plates (e.g., 25 lb) closest to the collar, then stack smaller ones outward — this helps bar balance and reduces torque on the sleeve.

- Use collars or spin-locks rated for your bar to prevent sliding; cheap clips may fail under higher loads.

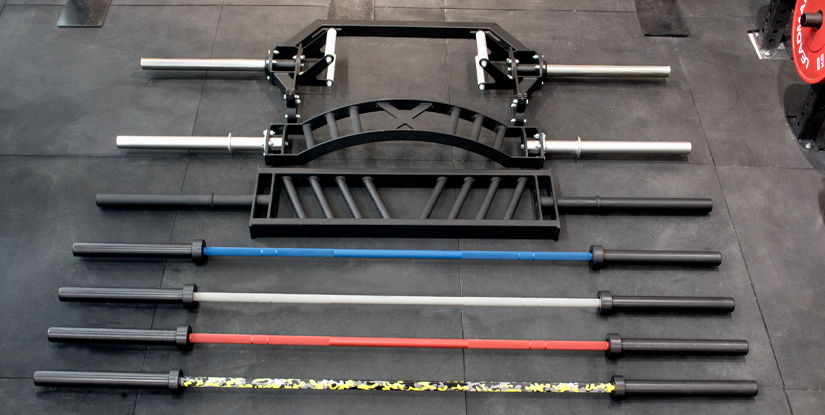

Visual elements description: imagine a simple diagram showing a side view of the bar sleeve: collar, 25 lb plate, 10 lb plate, 2.5 lb plate, followed by collar — largest-to-smallest stacking illustrated. This visual clarifies loading order and helps lifters count quickly when adding weight.

Step-by-Step: Loading and Balancing for Safety and Performance

Loading a standard barbell correctly is a routine that reduces risk and optimizes training. Follow this step-by-step guide every time:

- Place the bar on a rack or bench at comfortable height. If floor loading (deadlifts), maintain a safe posture and clear space.

- Confirm barbell empty weight by weighing it first if possible; mark it mentally (e.g., “15 lb bar”).

- Plan total load and calculate plates per side: (Target weight − bar weight) ÷ 2 = weight per sleeve.

- Load the largest plates first, sliding them fully onto the sleeve until seated against the shoulder of the sleeve.

- Add progressively smaller plates until you reach the desired per-side mass.

- Secure with appropriate collars or spin-locks; tighten until plates cannot move but avoid overtightening threaded collars (which can bind).

- Visually confirm symmetry and give the bar a small roll to detect imbalance. If it wobbles, unload and recount plates.

- Perform a warm-up set with a lighter load to test setup and movement pattern before going heavy.

Practical tip: write planned loads on a dry-erase board near your station. For high-frequency training, preloading two bars with typical working weights reduces setup time and keeps sessions efficient.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What exactly qualifies as a "standard" barbell and how does it differ from an Olympic bar? A: A standard barbell typically has a 1" (≈25 mm) sleeve diameter and is shorter and lighter (12–25 lb) than Olympic bars, which have 2" sleeves and weigh ≈44–45 lb. The sleeve diameter determines which plates fit — standard plates will not fit Olympic sleeves and vice versa.

Q2: How many pounds of plates do I need to get started? A: For most beginners, a 100–150 lb plate inventory plus a light standard bar (15–25 lb) covers progression for months. That might include 2×25 lb, 2×10 lb, 2×5 lb, 2×2.5 lb, and 2×1.25 lb plates to allow small increments.

Q3: Can I do serious strength training on a standard barbell? A: Yes, many people build significant strength using standard bars, especially for presses and rows. For very heavy deadlifts and competitive lifts, an Olympic bar offers better durability and sleeve capacity.

Q4: Are rubber-coated plates worth the extra cost? A: If you train indoors on hardwood or share walls with neighbors, rubber-coated plates reduce noise and floor damage. They also tend to be more durable against chipping.

Q5: How do I microload a standard barbell when plate increments are large? A: Buy fractional plates (0.5–1 lb) or use small weight increments like 1.25 lb plates which provide 2.5 lb total jumps. Another option is to manipulate variables like reps, tempo, and rest to progress without adding large weight jumps.

Q6: How should I store standard plates to maximize longevity? A: Store plates vertically on a rack or on a weighted plate tree; avoid moisture, wipe down cast iron plates occasionally, and keep rubber-coated plates off direct sunlight to preserve material.

Q7: What safety gear is essential when using a standard barbell? A: Collars or spin-locks, good lifting shoes, and an appropriate rack or bench are essential. Use bumper mats for heavy drops and spotters for max attempts on presses.

Q8: When should I upgrade from a standard barbell to an Olympic setup? A: Upgrade if you reach sleeve capacity limits, need better bar whip for dynamic lifts, or want to standardize with competitive lifting equipment. If you’re repeatedly adding >300 lb total on compound lifts and run out of sleeve space, consider an Olympic upgrade.