a personal trainer designs exercise plans

Assessment, Goals, and Baseline Data

A robust exercise plan starts long before a single rep is counted. For a personal trainer, the design process begins with a systematic intake that captures medical history, current fitness level, lifestyle factors, and personal goals. This foundation ensures safety, relevance, and sustainable progress. In practice, you map risk factors, identify movement limitations, and establish metrics that will guide programming and evaluation. A structured assessment also helps maintain accountability, fosters client buy-in, and provides concrete milestones that demonstrate tangible results over time.

Key components of the assessment phase include a comprehensive client interview, a risk-screening protocol, a movement screen, and baseline performance testing. The interview clarifies contraindications, past injuries, medications, sleep quality, nutrition habits, and time availability. The movement screen reveals compensations and asymmetries that influence exercise selection. Baseline tests—such as the push-up or plank for endurance, a submaximal squat or hinge for strength, and a simple cardio test like a 3-minute step test—offer objective data to compare against after weeks of training. Collecting data formally (e.g., in a client management system) enhances consistency and allows you to track trends with charts and dashboards over time.

Client Assessment Protocol

Structured intake steps create a repeatable framework that reduces ambiguity and increases safety.

- Medical history and medications: capture chronic conditions, allergies, surgeries, and current medications that affect exercise tolerance.

- Risk stratification: use a PAR-Q or equivalent tool to identify clients who require medical clearance.

- Movement screen: assess fundamental patterns (squat, hinge, lunge, push, pull, rotation) to spot mobility or stability issues.

- Baseline performance metrics: select simple, repeatable tests (e.g., timed push-ups, number of bodyweight squats in 60 seconds, waist-to-hip ratio, resting heart rate).

- Lifestyle and constraints: document work schedule, stress, sleep, and access to equipment.

- SMART initial goals: define 1–3 clear targets with timelines that align with the client’s asymmetries, capabilities, and priorities.

Practical tip: start every program with a 15–20 minute onboarding session that includes a movement demonstration, explanation of the plan, and an agreement on how progress will be tracked. This builds trust and reduces early dropouts.

Defining Realistic Goals and Milestones

Goal setting should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound (SMART). For instance, a client aiming to improve function for daily activities might target reducing knee pain by 25% and performing 12 push-ups without pain within 8 weeks. A competitive athlete might aim to increase 1RM back squat by 10–15% over 12 weeks, with a secondary goal of shaving 2–3% body fat. In practice, translate goals into weekly targets and mini-milestones—e.g., achieve a 2–4% weekly improvement in load or repetitions for four consecutive weeks before progressing. Document these milestones in the client’s plan and revisit them during weekly check-ins to adjust as needed.

Baseline Data and Metrics

Baseline data anchors program design and provides a reference for progress. Consider collecting both physical and functional metrics:

- Body composition: skinfold or bioelectrical impedance when available; otherwise track waist circumference monthly.

- Strength: 1–3 simple lifts (e.g., squat, push, hinge) with estimated 1RM or submaximal testing.

- Endurance: number of push-ups or planks in a minute, or a 2–3 minute cardio test (step test, cycle ergometer).

- Mobility and stability: hip flexor flexibility, ankle dorsiflexion, shoulder external rotation range.

- Functional matrices: daily activity levels, step counts, sleep duration, and perceived exertion (RPE) for workouts.

Practical tip: store baseline data in a centralized system and link each metric to a visual dashboard. Use charts for clients to visually track progress, not just numbers on a page.

Case Study: New Client Intake

Anna, a 34-year-old desk worker, sought sustainable fat loss and improved glute strength. Baseline data showed a 28% body fat estimate, a 12-week goal to reach under 25% body fat, a plank hold of 25 seconds, and a squat depth that barely reached parallel. The intake established a 12-week plan with three microcycles, prioritizing full-body strength, movement quality, and gradual fat loss. Within 8 weeks, Anna achieved 60 seconds of planking and improved squat depth, with a 2.8% decrease in body fat. The intake phase demonstrated how precise assessment and realistic milestones translate into measurable progress.

How can an exercise routine creator help you design personalized workout plans efficiently?

Program Design, Periodization, and Progression

Designing an exercise plan that travels from foundation to peak performance requires a clear periodization framework, thoughtful exercise selection, and a robust progression strategy. The goal is to maximize client outcomes while reducing injury risk and fatigue. Periodization provides structure for adaptation—ending cycles with reflection, deloads, and adjustments based on progress and life events. A well-designed plan also emphasizes movement quality, progressive overload, and data-driven adjustments. For most clients, a macrocycle of 12–16 weeks is a practical length that balances adaptation with motivation and life schedules. Within that macrocycle, mesocycles typically run 4 weeks each, and microcycles span one week. This structure supports clear phases: foundational stability, hypertrophy or strength development, and performance or conditioning peaks. A practical calendar helps clients anticipate changes and stay engaged.

Periodization Framework: Macro, Mes, and Microcycles

Illustrative 12-week example:

- Macrocycle: 12 weeks (overall plan and goals)

- Mesocycle 1 (Weeks 1–4): Foundation and movement quality; higher repetitions, lower load

- Mesocycle 2 (Weeks 5–8): Strength development; progressive overload with moderate loads

- Mesocycle 3 (Weeks 9–12): Performance and conditioning; sharper power and conditioning work

In practice, adapt to the client’s schedule and recovery. If a client travels often, incorporate portable equipment and home-based routines. Always schedule a deload week every 4–6 weeks to reduce accumulated fatigue and facilitate adaptation.

Exercise Selection and Programming Blocks

Design exercise blocks around major movement patterns: squat, hinge, push, pull, lunge, carry, and core. Prioritize multi-joint, high-kinetic-chain movements for efficiency and functional carryover, while adding isolated exercises to address specific weaknesses or goals. A typical week might include:

- 2–3 resistance days focusing on compound lifts (e.g., squats, deadlifts, bench presses) with progressive loading

- 1–2 days of accessory work targeting corrective mobility and stability

- 2–3 days of conditioning (steady-state cardio, intervals, or circuit training)

- Flexibility and mobility work integrated into cool-downs

Programming blocks should align with the client’s goals. For fat loss, emphasize higher work capacity and metabolic conditioning. For strength, emphasize progressive overload on key lifts with more volume early in the cycle. Example weekly plan: Monday (lower body), Tuesday (upper body), Thursday (conditioning), Friday (full-body strength/pp), Saturday (mobility or active recovery).

Progression, Regression, and Injury Prevention

Progression is the engine of adaptation. Use gradual overload—increase resistance by 2–5% per week, or add 1–2 reps per set before adding weight. When progression stalls, swap stimuluses: change tempo, adjust volume, or alter exercise variations. Regression strategies are essential for clients with injuries or movement limitations. Options include lowering load, replacing high-impact movements with low-impact alternatives, and focusing on mobility for restricted joints. Injury prevention sits at the core: proper warm-ups, load management, balanced training across all muscle groups, and ensuring adequate recovery time. Maintain open lines of communication for pain signals and adjust plans promptly if symptoms arise.

Monitoring, Feedback, and Adaptation

Effective monitoring combines objective data with subjective feedback. Track weekly metrics such as load (weight lifted), volume (sets x reps), RPE, and sleep; pair these with progress photos or circumference measurements for a visual trend. Use simple dashboards; review progress with clients during weekly check-ins and adjust the upcoming microcycle accordingly. When a plateau appears, consider deloads, microcycle variants, or a temporary shift in training emphasis to rekindle progress.

Case Study: Intermediate Client Transformation

Sam, a 42-year-old client with a sedentary background, aimed to lose fat and gain functional strength. Over 12 weeks, the plan moved from focusing on movement quality and conditioning to targeted strength work, culminating in a 15% improvement in total strength (assessed by a 3-lap circuit and 1RM estimates) and a 4% reduction in body fat percentage. The program integrated two deload weeks and three mobility sessions, illustrating how progressive overload, balanced programming, and recovery deliver consistent gains for an intermediate learner.

How Can You Create an Effective Exercise Workout Plan That Delivers Real Results?

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How long should a personalized training plan take to show results? A1: Most clients begin seeing meaningful changes within 4–8 weeks, with more pronounced strength and body composition shifts by 12–16 weeks, depending on initial fitness level, adherence, and goals.

Q2: How do you assess a client’s starting point?

A2: Use a structured intake, movement screen, baseline tests, and lifestyle assessments. Combine objective metrics with client-reported readiness and pain levels to calibrate the plan.

Q3: How do you tailor plans for weight loss versus muscle gain?

A3: Weight loss emphasizes caloric balance, conditioning, and higher training volume; muscle gain prioritizes progressive overload, higher protein targets, and strategic resistance training emphasis on compound lifts.

Q4: How often should progression occur?

A4: In novices, progress weekly or biweekly is common; for intermediate lifters, progression may occur every 2–4 weeks depending on adaptation and recovery.

Q5: How do you handle injuries within a plan?

A5: Implement a stepped approach: symptom monitoring, regression to safer movements, load management, and collaboration with healthcare professionals when needed.

Q6: How do you adjust plans for aging clients?

A6: Prioritize joints-friendly movements, longer recovery windows, and functional goals. Emphasize mobility, balance, and sustainable strength work with gradual progression.

Q7: How does nutrition integrate with exercise plans?

A7: Nutrition supports goals; align caloric intake, protein targets, and hydration with training demands. Coordinate with nutrition professionals when possible for complex goals.

Q8: What tools help clients stay accountable?

A8: Training logs, mobile apps, scheduled check-ins, wearable data, and clear weekly goals keep clients engaged and responsible for adherence.

Q9: How should deload weeks be used?

A9: Deload weeks reduce fatigue and facilitate adaptation. They typically involve reduced volume or intensity and can be timed after 4–6 weeks of progressive training.

Q10: How do you handle plateau scenarios?

A10: Modify variables such as tempo, volume, exercise variation, or training frequency. Introduce short-term goals to re-ignite motivation and monitor response.

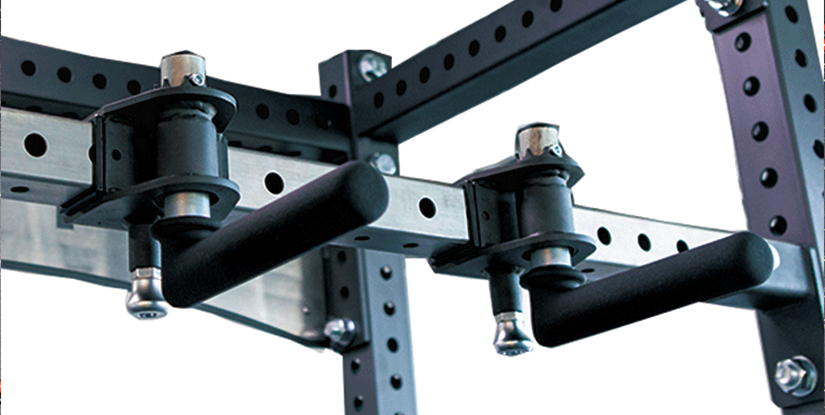

Q11: What equipment is essential for most personalized plans?

A11: A basic kit includes resistance bands, adjustable dumbbells, a compact bench or step, a mat, and a cardio option (treadmill, bike, or jump rope). Programs should be adaptable to home or gym environments.

Q12: How do you measure success beyond numbers?

A12: Consider functional improvements, pain reduction, confidence growth, sleep quality, and daily activity levels. Subjective well-being is a core indicator of long-term adherence and health.